|

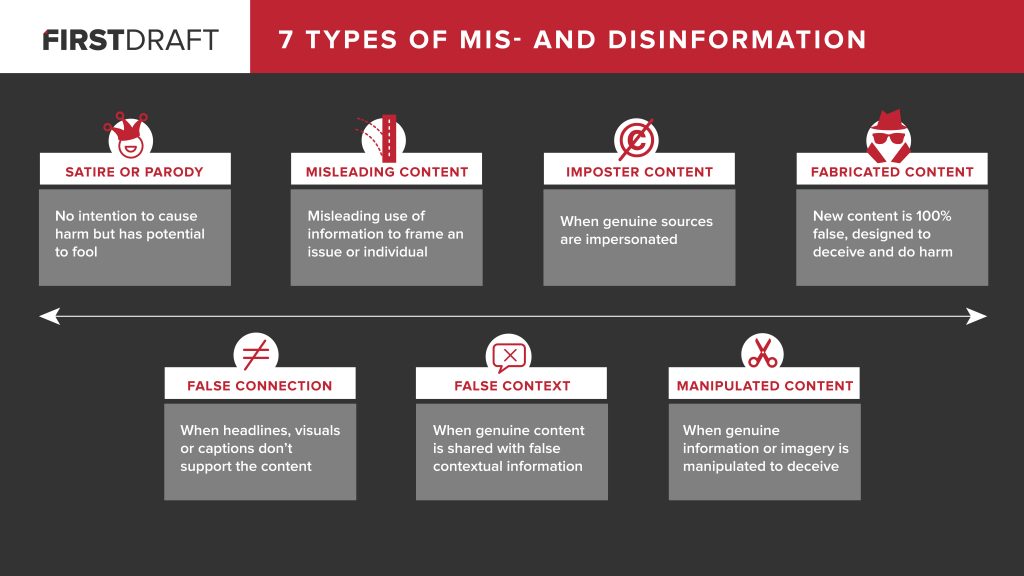

"Are some of the newsroom's most prized values contributing to journalism's continuing decline in credibility?” Tim Porter poses this question in his 2005 essay “New values for a new age of journalism.” He outlines “old” values (including competition, speed and individualism) and argues these concepts must be replaced with new values (such as context, discipline and collaboration) more reflective of the information age. Written before the advent of the iPhone and social media, Porter’s essay now seems oddly prescient. It was hard to get the “scoop” on breaking news in 2005, but it’s nearly impossible in 2017 when anyone can Snap, Tweet or FacebookLive an event as it happens. As I discussed in my previous post, what brings value to good journalism — whether professional or scholastic — is context, depth and verification. This also provides a starting point for a discussion of “fake news.” The term gained prominence during the 2016 presidential campaign to describe the completely untrue stories that circulated on social media platforms and that some claimed greatly affected the outcome of the election (though a study conducted by researchers at Stanford and NYU suggests that this was not the case). However, in the wake of Trump’s election and his avowed war with the media, this term has, Washington Post reporter Callum Borchers wrote on Feb. 9, “lost all meaning.” In this opinion piece, Borchers asserts that "conservatives — led by President Trump — have hijacked the term and sought to redefine it as, basically, any reporting they don't like. At the extreme end of absurdity, Trump actually asserted on Monday that 'any negative polls are fake news.’” So should we stop even trying to talk about fake news with our students? No. But we do need to talk about it with more nuance. In a recent essay for First Draft News, Claire Wardle writes, "By now we’ve all agreed the term 'fake news' is unhelpful, but without an alternative, we’re left awkwardly using air quotes whenever we utter the phrase. The reason we’re struggling with a replacement is because this is about more than news, it’s about the entire information ecosystem. And the term fake doesn’t begin to describe the complexity of the different types of misinformation (the inadvertent sharing of false information) and disinformation (the deliberate creation and sharing of information known to be false)." We must consider "the different types of content being created or shared, the motivations of those who created it and the ways that content is being disseminated,” she writes, in order to "understand the current information ecosystem”:  Claire Wardle’s infographic describes seven types of mis- and disinformation she sees in our current information ecosystem. According to the website, Wardle is leading strategy and research for First Draft News and is the former research director at the @TowCenter at Columbia J-School. To read her original article, go to http://tinyurl.com/gllx5m2 Her essay is complex and worth a careful read, so I’m not going to try to summarize it all here, but it left me thinking about how her analysis connects to Porter’s essay about journalism needing new values.

Let me be clear — I am in no way equating mistakes made by reputable journalists and then corrected as the kind of disinformation spread through fabricated articles. However, I do think that those older journalistic values of competition and individualism contribute to accidental misinformation that can have real world consequences. Just think about how the desire to break the story first has contributed to reputable news outlets identifying terrorism suspects who turned out to be innocent, such as Richard Jewell, Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, Mark Hughes or Ryan Lanza. Everyone makes mistakes, even journalists who work so hard to tell the truth. Student journalists are bound to make many, and that is all right. We learn the most when we make mistakes. But steering our students towards Porter's new values may help them to avoid the temptation to publish before verifying or to go it alone in order to be the first to print rather than seeking feedback that might prevent them from making a mistake. Credibility is the most precious currency for journalists, especially in our current political climate. Porter’s essay was written 12 years ago, but it has never been more relevant than it is right now.

1 Comment

Lindsay Coppens

3/5/2017 08:38:51 am

I really appreciate how you wove ideas from all of those readings together. I, too, was struck by Wardle's analysis and appreciate the nuances of different types of mis- & dis-information.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About“And though she be but little, she is fierce!” -A Midsummer Night’s Dream Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed