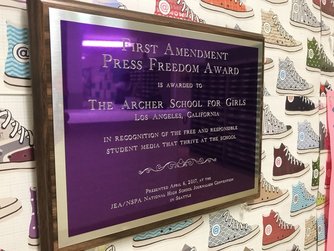

My school's 2017 First Amendment Press Freedom Award hangs on the way in the upper school. Allowing students final editorial say in all content provides them with a real citizenship experience, but it also means adults letting go of the urge to shield and protect and instead empowering their voices. My school's 2017 First Amendment Press Freedom Award hangs on the way in the upper school. Allowing students final editorial say in all content provides them with a real citizenship experience, but it also means adults letting go of the urge to shield and protect and instead empowering their voices. Teachers and administrators want to help our students. We want to give them the tools to succeed, but we also sometimes want to protect them — to shield them from harsh truths and difficult situations. When I'm teaching my journalism students about the social role of the mass media and their own societal role as young journalists, I also think a lot about my role as their adviser. I argued earlier this year that if we want students to value citizenship, we must let them be citizens, but citizenship isn't easy, and it isn't "safe." Citizenship means taking an active role, speaking truth to power, and taking risks. If I want them to learn to be citizens, I must resist that urge to shield and protect and instead empower them to make their own decisions and take responsibility for the outcome.

0 Comments

David Bornstein co-authors the "Fixes" column in the New York Times, a column focused on solutions journalism. In his 2012 TED talk above, Bornstein explains why he has pursued solutions in his investigative journalism rather than simply focusing on the problem.

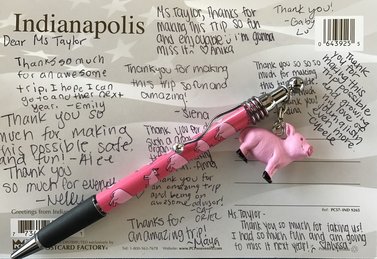

Bornstein argues that consistently negative feedback alienates journalism's desired audience. How many of us, he wonders, have stopped watching the nightly news because it feels like such an unrelenting parade of misery? He has a point. Yet quick fluff hero stories — a firefighter saving a kitten from a tree — are also not the answer. He posits that serious journalism can investigate solutions as easily as it can problems, and argues that news producers need to devote equal resources to this alternative approach. I really like this perspective, as it charts an important middle ground between gloom and fluff, and I think journalism students would benefit from watching this video and talking about the balance of their own articles.  My publications students gave me this postcard after we attended the fall National High School Journalism Convention in Indianapolis. Conventions like this bring students who are already engaged in journalism together, but how can we get the rest of the school excited? My publications students gave me this postcard after we attended the fall National High School Journalism Convention in Indianapolis. Conventions like this bring students who are already engaged in journalism together, but how can we get the rest of the school excited? I wish journalism was a required core subject. I wish we could help every high school student dive into the process and joy of determining what is newsworthy, learning what constitutes good reporting versus repeating rumors, developing the confidence to interview adults and peers and ask hard questions, considering the foundational pillars of ethical journalism, writing and editing and editing and editing and proofreading until an article is truly clear, and learning all the other skills and ways of thinking that happen naturally when a student is actively engaged in news-production. Since every student at the school can't be on staff, however, how can we get the rest of the school engaged in news?  A screenshot of the Washington Post story about the team of student reporters who uncovered the truth about their new principal. A screenshot of the Washington Post story about the team of student reporters who uncovered the truth about their new principal. I woke up this morning to multiple social media notifications from friends tagging me to make sure I saw this story in the Washington Post. The article details how a group of six student reporters for the Booster Redux at Pittsburg High School in southeastern Kansas started researching their new principal and uncovered some major discrepancies in her educational record, which eventually led to her resignation. You can (and should!) read the story for specific details about what they uncovered, but for me the story reaffirmed how crucial it is for students to be empowered to be investigators and watchdogs, not just public relations tools. |

About“And though she be but little, she is fierce!” -A Midsummer Night’s Dream Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed