|

Keywords: advising, multimedia, journalism

When I started advising a scholastic newspaper, I was pretty sure that if I learned how to write like a journalist, I would be well on my way to a successful program. I wasn’t entirely wrong. Mastering news-writing skills is crucial for new journalists, and learning to write like a journalist means learning how to write well. As Tim Harrower points out in “Inside Reporting,” the lessons Hemingway learned during his time on the Kansas City Star “were the best rules [he] ever learned for the business of writing.” But the days when narrow rows of text ruled journalism are past. Today’s journalists need more than words to engage and inform their readerships.

0 Comments

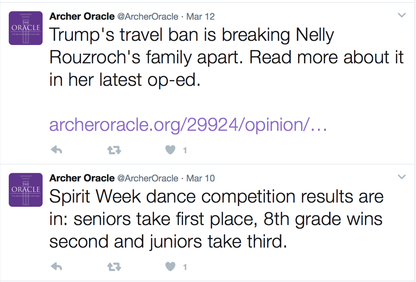

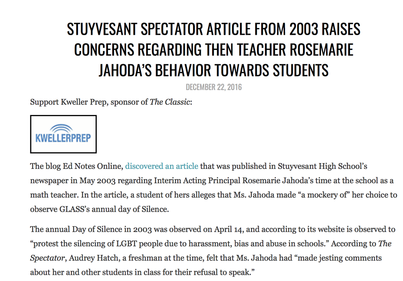

Two recent posts from my student journalists' news site Twitter. They use social media to share recently published stories and report on breaking news. Two recent posts from my student journalists' news site Twitter. They use social media to share recently published stories and report on breaking news. Social media has had such a profound effect on journalism that it's sometimes hard to remember how traditional news functioned before it. Reading this 2009 MediaShift article is a powerful reminder that Twitter wasn't always the source of breaking news. In fact, as author Julie Posetti wrote just eight years ago, "Some employers are either so afraid of the platform or so disdainful about its journalistic potential that they've tried to bar their reporters from even accessing Twitter in the workplace." Not accessing Twitter in the newsroom? It's laughable now. Yet for some high school newsrooms, this is still the case.  A screenshot of one of the stories reported by Townsend Harris High School's student newspaper, The Classic. Acting as watchdog journalists, these student journalists have written a series of stories about the controversy surrounding the school's interim principal, Rosemarie Jahoda. A screenshot of one of the stories reported by Townsend Harris High School's student newspaper, The Classic. Acting as watchdog journalists, these student journalists have written a series of stories about the controversy surrounding the school's interim principal, Rosemarie Jahoda. One of the most important roles of a free press in a journalistic society is to act as a watchdog, to keep an eye on those in power and to ensure that power is not being misused. Although this role is more prominent among professionals, student journalists willing to put in the necessary time and research can be powerful watchdogs for their communities. In his Poynter article "Watchdog Culture: Why You Need it, How You Can Build it," Butch Ward describes a 2005 conference for media professionals and public service journalism organizations about the importance of creating a watchdog culture in newsrooms. "Are some of the newsroom's most prized values contributing to journalism's continuing decline in credibility?” Tim Porter poses this question in his 2005 essay “New values for a new age of journalism.” He outlines “old” values (including competition, speed and individualism) and argues these concepts must be replaced with new values (such as context, discipline and collaboration) more reflective of the information age.

Written before the advent of the iPhone and social media, Porter’s essay now seems oddly prescient. It was hard to get the “scoop” on breaking news in 2005, but it’s nearly impossible in 2017 when anyone can Snap, Tweet or FacebookLive an event as it happens. As I discussed in my previous post, what brings value to good journalism — whether professional or scholastic — is context, depth and verification. This also provides a starting point for a discussion of “fake news.”  A screenshot of a recent article about anti-Semitic messages in a local community by one of my student journalists. I’ve challenged my reporters to think about how they can move from conveying information to helping readers’ understanding. A screenshot of a recent article about anti-Semitic messages in a local community by one of my student journalists. I’ve challenged my reporters to think about how they can move from conveying information to helping readers’ understanding. My student newspaper staff has a dilemma: how can they get their peers to read the paper when so much of the information in our articles is already known? They are coming up against a problem professional journalists have been struggling with for years. In the old days (I won’t call them good, as I think that’s always relative), news producers — whether newspaper, radio or broadcast — were the source of information. News consumers found out about terrorists attack and new government policies when they opened the morning paper or turned on the evening news. With the advent of the Internet and social media, however, those gatekeepers lost control. Now people have more information than they know what to do with. This flood of data creates a number of problems — especially in terms of helping people separate fact from fiction — but I want to focus today on the issue it creates in terms of engagement. |

About“And though she be but little, she is fierce!” -A Midsummer Night’s Dream Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed