A screenshot of the Washington Post story about the team of student reporters who uncovered the truth about their new principal. A screenshot of the Washington Post story about the team of student reporters who uncovered the truth about their new principal. I woke up this morning to multiple social media notifications from friends tagging me to make sure I saw this story in the Washington Post. The article details how a group of six student reporters for the Booster Redux at Pittsburg High School in southeastern Kansas started researching their new principal and uncovered some major discrepancies in her educational record, which eventually led to her resignation. You can (and should!) read the story for specific details about what they uncovered, but for me the story reaffirmed how crucial it is for students to be empowered to be investigators and watchdogs, not just public relations tools.

1 Comment

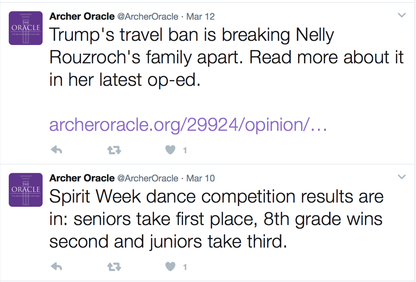

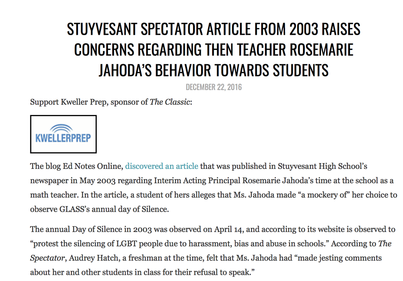

Two recent posts from my student journalists' news site Twitter. They use social media to share recently published stories and report on breaking news. Two recent posts from my student journalists' news site Twitter. They use social media to share recently published stories and report on breaking news. Social media has had such a profound effect on journalism that it's sometimes hard to remember how traditional news functioned before it. Reading this 2009 MediaShift article is a powerful reminder that Twitter wasn't always the source of breaking news. In fact, as author Julie Posetti wrote just eight years ago, "Some employers are either so afraid of the platform or so disdainful about its journalistic potential that they've tried to bar their reporters from even accessing Twitter in the workplace." Not accessing Twitter in the newsroom? It's laughable now. Yet for some high school newsrooms, this is still the case.  A screenshot of one of the stories reported by Townsend Harris High School's student newspaper, The Classic. Acting as watchdog journalists, these student journalists have written a series of stories about the controversy surrounding the school's interim principal, Rosemarie Jahoda. A screenshot of one of the stories reported by Townsend Harris High School's student newspaper, The Classic. Acting as watchdog journalists, these student journalists have written a series of stories about the controversy surrounding the school's interim principal, Rosemarie Jahoda. One of the most important roles of a free press in a journalistic society is to act as a watchdog, to keep an eye on those in power and to ensure that power is not being misused. Although this role is more prominent among professionals, student journalists willing to put in the necessary time and research can be powerful watchdogs for their communities. In his Poynter article "Watchdog Culture: Why You Need it, How You Can Build it," Butch Ward describes a 2005 conference for media professionals and public service journalism organizations about the importance of creating a watchdog culture in newsrooms.  A screenshot of a recent article about anti-Semitic messages in a local community by one of my student journalists. I’ve challenged my reporters to think about how they can move from conveying information to helping readers’ understanding. A screenshot of a recent article about anti-Semitic messages in a local community by one of my student journalists. I’ve challenged my reporters to think about how they can move from conveying information to helping readers’ understanding. My student newspaper staff has a dilemma: how can they get their peers to read the paper when so much of the information in our articles is already known? They are coming up against a problem professional journalists have been struggling with for years. In the old days (I won’t call them good, as I think that’s always relative), news producers — whether newspaper, radio or broadcast — were the source of information. News consumers found out about terrorists attack and new government policies when they opened the morning paper or turned on the evening news. With the advent of the Internet and social media, however, those gatekeepers lost control. Now people have more information than they know what to do with. This flood of data creates a number of problems — especially in terms of helping people separate fact from fiction — but I want to focus today on the issue it creates in terms of engagement. One of the biggest challenges I face as a journalism adviser is convincing my students that email interviews need to be a last resort rather than their go-to.

I get it — emails are quick and easy. Write a few questions, get responses in complete sentences back. No need to transcribe or deal with awkward verbal phrasings. Seems like a no-brainer. In a 2003 Poynter article, Jonathan Dube outlined some of the benefits of email interviews, then a relatively new journalistic tool: saving time, being efficient, creating a written record, providing time for the source to think and prepare, and working with people in different time zones or who write English better than they speak it. But he also pointed out potential pitfalls: not knowing who is replying (is this actually the superintendent, or did she just hand it off to an assistant?), not being able to follow up with more questions based on the direction of the interview, losing control of the interview transcript, missing out on body language and verbal cues that might provide more insight, and — ultimately — ending up with an interview that is unlikely to provide revealing or new information. |

About“And though she be but little, she is fierce!” -A Midsummer Night’s Dream Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed