A screenshot of the Washington Post story about the team of student reporters who uncovered the truth about their new principal. A screenshot of the Washington Post story about the team of student reporters who uncovered the truth about their new principal. I woke up this morning to multiple social media notifications from friends tagging me to make sure I saw this story in the Washington Post. The article details how a group of six student reporters for the Booster Redux at Pittsburg High School in southeastern Kansas started researching their new principal and uncovered some major discrepancies in her educational record, which eventually led to her resignation. You can (and should!) read the story for specific details about what they uncovered, but for me the story reaffirmed how crucial it is for students to be empowered to be investigators and watchdogs, not just public relations tools.

1 Comment

Two recent posts from my student journalists' news site Twitter. They use social media to share recently published stories and report on breaking news. Two recent posts from my student journalists' news site Twitter. They use social media to share recently published stories and report on breaking news. Social media has had such a profound effect on journalism that it's sometimes hard to remember how traditional news functioned before it. Reading this 2009 MediaShift article is a powerful reminder that Twitter wasn't always the source of breaking news. In fact, as author Julie Posetti wrote just eight years ago, "Some employers are either so afraid of the platform or so disdainful about its journalistic potential that they've tried to bar their reporters from even accessing Twitter in the workplace." Not accessing Twitter in the newsroom? It's laughable now. Yet for some high school newsrooms, this is still the case.  A screenshot of one of the stories reported by Townsend Harris High School's student newspaper, The Classic. Acting as watchdog journalists, these student journalists have written a series of stories about the controversy surrounding the school's interim principal, Rosemarie Jahoda. A screenshot of one of the stories reported by Townsend Harris High School's student newspaper, The Classic. Acting as watchdog journalists, these student journalists have written a series of stories about the controversy surrounding the school's interim principal, Rosemarie Jahoda. One of the most important roles of a free press in a journalistic society is to act as a watchdog, to keep an eye on those in power and to ensure that power is not being misused. Although this role is more prominent among professionals, student journalists willing to put in the necessary time and research can be powerful watchdogs for their communities. In his Poynter article "Watchdog Culture: Why You Need it, How You Can Build it," Butch Ward describes a 2005 conference for media professionals and public service journalism organizations about the importance of creating a watchdog culture in newsrooms. "Are some of the newsroom's most prized values contributing to journalism's continuing decline in credibility?” Tim Porter poses this question in his 2005 essay “New values for a new age of journalism.” He outlines “old” values (including competition, speed and individualism) and argues these concepts must be replaced with new values (such as context, discipline and collaboration) more reflective of the information age.

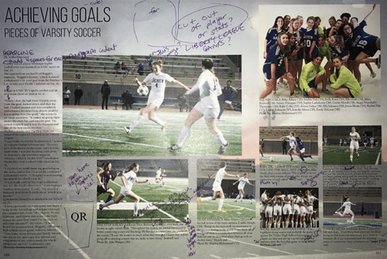

Written before the advent of the iPhone and social media, Porter’s essay now seems oddly prescient. It was hard to get the “scoop” on breaking news in 2005, but it’s nearly impossible in 2017 when anyone can Snap, Tweet or FacebookLive an event as it happens. As I discussed in my previous post, what brings value to good journalism — whether professional or scholastic — is context, depth and verification. This also provides a starting point for a discussion of “fake news.”  A draft of one of my student's yearbook spreads with feedback. Yearbook advisers and their students must decide how to handle sensitive subjects as they plan their coverage. A draft of one of my student's yearbook spreads with feedback. Yearbook advisers and their students must decide how to handle sensitive subjects as they plan their coverage. What is the purpose of a yearbook? Should it be a scrapbook of memories highlighting only the good times from the year, or should it reflect the full year’s story, including the rougher bits? As a newspaper adviser, the answer seems simple: we tell the whole story, even when it’s not pretty. Only reporting on the positive isn’t journalism — it's PR. And as I argued in my previous post, our students need to learn the habits and purpose of authentic journalism in their schools if we want them to understand the role of the professional press as a watchdog over the powerful after they graduate. True, a yearbook is not the same as a school paper. Many stories that work beautifully in the newspaper will not fit as well in a yearbook, But yearbooks are journalism, and yearbook staffers are journalists. If we treat our books as scrapbooks or collages, we miss an opportunity. Sally Renaud, writing for the publisher Walsworth, hates hearing, "Our school doesn’t have journalism. I just advise the yearbook.” She writes, "The fundamentals of journalism involve telling the story of communities, and no one does this better than the school yearbook.” Staffers need to understand basic news values — timeliness, proximity, prominence, impact and novelty — in order to determine what deserves a spread and what does not. They also need a solid foundation in journalistic skills: reporting, interviewing, writing, editing, graphic design and photojournalism, to name a few. Add to that a solid dose of journalistic ethics, and we have the recipe for a yearbook that tells the truth in a responsible and unique way. Aaron Manfull argues that a yearbook’s role in a larger school media program should be to serve as a recapper for the year — as the “historical record of the school,” yearbooks should take a broader view. "While there is definitely a place in the book for profiles and features,” he writes, "event recap coverage in the yearbook can take a little extra time and include a little more perspective of how the event played into the year as a whole." With that in mind, how should yearbooks recap sensitive topics? If we only include the positive — obfuscating the fact that the soccer team didn’t win a single game, for example — are we creating books that are, in essence, “fake news”? John Bowen, director of scholastic press rights for JEA and my current professor at Kent State University, posed this question to me recently, and it stopped me cold. I know that we should never lie in journalism, yet I am acutely aware of the pressure most independent school advisers feel to create a book that looks good on an admissions waiting area coffee table, a book that highlights everything positive about the school rather than focusing on the negative. Is there a middle ground? Walsworth’s protocol for covering sensitive issues offers some good suggestions, but it is also problematic. Should the students consider the relevance of the topic and whether it could potentially harm or endanger others? Absolutely. Should they be thoughtful and proactive in determining their approach? Definitely. But should they only publish what the community “accepts” and only tell the story if they can make it “hopeful”? Yikes. This advice makes me think of Ross Szabo’s book Behind Happy Faces, which examines the complexity of mental health in teenagers. "It’s far too common for people to hide their true feelings, go through the motions and put on a happy face to make others think everything is OK,” he writes, but "emotions can only be hidden for so long before they come out in negative ways.... It’s time to stop hiding behind a happy face and start talking about these issues.” Teenagers, and especially teenaged girls, are pressured to smile, be happy, buck up, little camper. I can’t help but feel that a yearbook that only highlights the positive reinforces this unhealthy message. I think the way to address the tough stuff in a yearbook is to reframe the outcome. Walsworth suggests the students “look to tell a story with a hopeful angle. How can this story be told so that it makes the student body and school community feel good about themselves, despite the negative or tragic issue?” [emphasis mine] What if instead of forcing “hope” into a story that may not have much, we instead look at solutions journalism? Let’s rework that advice: “Look to tell a story with an informative angle. How can this story be told so that it makes the student body and school community see potential solutions, despite the negative or tragic issue?" When they crack the spine open for the first time on distribution day, I want the yearbook to make our student body feel good — to smile and enjoy happy memories — but I don’t want them to be reading another form of fake news. We shouldn’t make the whole book a Debbie Downer, but it has to be all right to acknowledge the year had some bumps. I hope this is how we find a middle ground that honors both purposes of a yearbook: as a source for happy memories and an accurate historical record. |

About“And though she be but little, she is fierce!” -A Midsummer Night’s Dream Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed