A screenshot of a recent article about anti-Semitic messages in a local community by one of my student journalists. I’ve challenged my reporters to think about how they can move from conveying information to helping readers’ understanding. A screenshot of a recent article about anti-Semitic messages in a local community by one of my student journalists. I’ve challenged my reporters to think about how they can move from conveying information to helping readers’ understanding. My student newspaper staff has a dilemma: how can they get their peers to read the paper when so much of the information in our articles is already known? They are coming up against a problem professional journalists have been struggling with for years. In the old days (I won’t call them good, as I think that’s always relative), news producers — whether newspaper, radio or broadcast — were the source of information. News consumers found out about terrorists attack and new government policies when they opened the morning paper or turned on the evening news. With the advent of the Internet and social media, however, those gatekeepers lost control. Now people have more information than they know what to do with. This flood of data creates a number of problems — especially in terms of helping people separate fact from fiction — but I want to focus today on the issue it creates in terms of engagement.

2 Comments

One of the biggest challenges I face as a journalism adviser is convincing my students that email interviews need to be a last resort rather than their go-to.

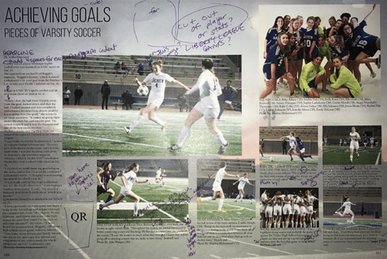

I get it — emails are quick and easy. Write a few questions, get responses in complete sentences back. No need to transcribe or deal with awkward verbal phrasings. Seems like a no-brainer. In a 2003 Poynter article, Jonathan Dube outlined some of the benefits of email interviews, then a relatively new journalistic tool: saving time, being efficient, creating a written record, providing time for the source to think and prepare, and working with people in different time zones or who write English better than they speak it. But he also pointed out potential pitfalls: not knowing who is replying (is this actually the superintendent, or did she just hand it off to an assistant?), not being able to follow up with more questions based on the direction of the interview, losing control of the interview transcript, missing out on body language and verbal cues that might provide more insight, and — ultimately — ending up with an interview that is unlikely to provide revealing or new information.  A draft of one of my student's yearbook spreads with feedback. Yearbook advisers and their students must decide how to handle sensitive subjects as they plan their coverage. A draft of one of my student's yearbook spreads with feedback. Yearbook advisers and their students must decide how to handle sensitive subjects as they plan their coverage. What is the purpose of a yearbook? Should it be a scrapbook of memories highlighting only the good times from the year, or should it reflect the full year’s story, including the rougher bits? As a newspaper adviser, the answer seems simple: we tell the whole story, even when it’s not pretty. Only reporting on the positive isn’t journalism — it's PR. And as I argued in my previous post, our students need to learn the habits and purpose of authentic journalism in their schools if we want them to understand the role of the professional press as a watchdog over the powerful after they graduate. True, a yearbook is not the same as a school paper. Many stories that work beautifully in the newspaper will not fit as well in a yearbook, But yearbooks are journalism, and yearbook staffers are journalists. If we treat our books as scrapbooks or collages, we miss an opportunity. Sally Renaud, writing for the publisher Walsworth, hates hearing, "Our school doesn’t have journalism. I just advise the yearbook.” She writes, "The fundamentals of journalism involve telling the story of communities, and no one does this better than the school yearbook.” Staffers need to understand basic news values — timeliness, proximity, prominence, impact and novelty — in order to determine what deserves a spread and what does not. They also need a solid foundation in journalistic skills: reporting, interviewing, writing, editing, graphic design and photojournalism, to name a few. Add to that a solid dose of journalistic ethics, and we have the recipe for a yearbook that tells the truth in a responsible and unique way. Aaron Manfull argues that a yearbook’s role in a larger school media program should be to serve as a recapper for the year — as the “historical record of the school,” yearbooks should take a broader view. "While there is definitely a place in the book for profiles and features,” he writes, "event recap coverage in the yearbook can take a little extra time and include a little more perspective of how the event played into the year as a whole." With that in mind, how should yearbooks recap sensitive topics? If we only include the positive — obfuscating the fact that the soccer team didn’t win a single game, for example — are we creating books that are, in essence, “fake news”? John Bowen, director of scholastic press rights for JEA and my current professor at Kent State University, posed this question to me recently, and it stopped me cold. I know that we should never lie in journalism, yet I am acutely aware of the pressure most independent school advisers feel to create a book that looks good on an admissions waiting area coffee table, a book that highlights everything positive about the school rather than focusing on the negative. Is there a middle ground? Walsworth’s protocol for covering sensitive issues offers some good suggestions, but it is also problematic. Should the students consider the relevance of the topic and whether it could potentially harm or endanger others? Absolutely. Should they be thoughtful and proactive in determining their approach? Definitely. But should they only publish what the community “accepts” and only tell the story if they can make it “hopeful”? Yikes. This advice makes me think of Ross Szabo’s book Behind Happy Faces, which examines the complexity of mental health in teenagers. "It’s far too common for people to hide their true feelings, go through the motions and put on a happy face to make others think everything is OK,” he writes, but "emotions can only be hidden for so long before they come out in negative ways.... It’s time to stop hiding behind a happy face and start talking about these issues.” Teenagers, and especially teenaged girls, are pressured to smile, be happy, buck up, little camper. I can’t help but feel that a yearbook that only highlights the positive reinforces this unhealthy message. I think the way to address the tough stuff in a yearbook is to reframe the outcome. Walsworth suggests the students “look to tell a story with a hopeful angle. How can this story be told so that it makes the student body and school community feel good about themselves, despite the negative or tragic issue?” [emphasis mine] What if instead of forcing “hope” into a story that may not have much, we instead look at solutions journalism? Let’s rework that advice: “Look to tell a story with an informative angle. How can this story be told so that it makes the student body and school community see potential solutions, despite the negative or tragic issue?" When they crack the spine open for the first time on distribution day, I want the yearbook to make our student body feel good — to smile and enjoy happy memories — but I don’t want them to be reading another form of fake news. We shouldn’t make the whole book a Debbie Downer, but it has to be all right to acknowledge the year had some bumps. I hope this is how we find a middle ground that honors both purposes of a yearbook: as a source for happy memories and an accurate historical record. With great power comes great responsibility (and other superhero benefits of a free student press)2/5/2017  A group of my publications students, our upper school director and the two advisers pose after receiving the 2016 First Amendment Free Press Award at the National High School Journalism Convention in Los Angeles. According to the presenters, we were one of only three independent schools to ever win this award. A group of my publications students, our upper school director and the two advisers pose after receiving the 2016 First Amendment Free Press Award at the National High School Journalism Convention in Los Angeles. According to the presenters, we were one of only three independent schools to ever win this award. Pop quiz: can you name the five freedoms of the First Amendment? According to the Newseum’s 2016 State of the First Amendment Survey, 39 percent of Americans can’t name a single one. I couldn’t name more than a few when I left high school, but my current high school student journalists know all five. (For the record: speech, religion, petition, assembly and press.) Knowing these rights is especially important for high school students on the cusp of adulthood, ready to leave the school bubble and embark on lives as citizens. How can we inculcate a love of citizenship in teenagers who are already cynical about the mess left behind by adults? I believe a place to start is allowing them to BE citizens within the school walls. I’m not going to give an entire overview of the First Amendment in public schools here, but I will say it’s a lot more complicated than you might think. Heading over to the Student Press Law Center’s Top 10 High School FAQ’s is a place to start, but it’s not a stopping point. A student’s free speech rights depends not only on the First Amendment and the major Supreme Court rulings (Tinker v. Des Moines and Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, to name the two most impactful), but also on individual state laws, which may expand those rights beyond the Hazelwood standard. The first of these was the California Student Free Expression Law, enacted before the Hazelwood ruling, but many states have added statutes like this in years since. To find out whether an instance of censorship of the school press is legal, I recommend using this helpful SPLC First Amendment Rights of High School Journalists chart. But for students in private schools — unless they attend a non-religious school in California, in which case Leonard Law offers unique protection for their speech— the First Amendment is irrelevant. Faculty and staff at independent schools are not representatives of the government, so they are not governed by the First Amendment. And honestly, though the law is a compelling reason, it is in some ways a much less compelling reason than the pedagogical and national benefits of freeing our scholastic presses. As Uncle Ben told Peter Parker in the 2002 film Spider-Man, “With great power comes great responsibility,” and therein lies the heart of this lesson: if student journalists don’t have real power, they will not learn the real responsibilities of citizenship. "Without journalism, democratic life dies from lack of oxygen,” Roy Peter Clark, senior scholar at the Pointer Institute, writes. "Without democracy, journalism loses its heartbeat. Without a serious study of journalism there can be no understanding of citizenship, democracy or community." I am fortunate to work in a school that honors student journalism and gives our student editorial board the final say in all content decisions for their publications, and I’ve seen the lasting benefits of this firsthand. Student journalists need guidance, no doubt, but that is why it is so crucial to hire a knowledgable journalism adviser who can teach not only core journalistic skills — interviewing, reporting, research, writing and editing — but also values and ethics. My role as an adviser is not to tell students what they can and cannot write, but rather to provide context and conversation to help them to see the tremendous responsibilities they take on and opportunities they have as journalists. If students are subject to prior review, where someone other than the staff and adviser reads their work before they are allowed to publish it, they lack a sense of ownership. Why should they worry about making sure a story is ethical or thorough if an adult is going to do it for them? But when students know that they are fully responsible — ethically and legally — for everything they publish, editorial conversations become much richer. I see this in action all the time with my own staff. Recently, one of my students wrote a column about her personal experience at the Los Angeles Women’s March. In this piece, she referenced putting on her “pussyhat” before leaving for the Metro. As the editors and I gave her feedback, a thoughtful conversation about the term and our student audience emerged. Was the p-word too controversial to print? Would following their own staff manual guidelines and using "p----hat” diminish the historical relevance of the movement? Should they just allude to the hat (“my pink knitted hat”) rather than naming it? Did the fact we are a grades 6-12 school (though the staff is entirely upper school) matter in this conversation? Did censoring themselves in this way set a bad precedent? This is their paper, and this was their decision. Those facts meant that this conversation had real weight. It wasn’t just a hypothetical situation — their decision would have real impact and consequences. In the end, they decided to keep the reference and follow their staff manual guidelines (“p----hat.”) but hyperlink to a source explaining the Pussyhat Project. No adult in the community needed to censor them; they reached an ethical decision on their own, and, more importantly, they will remember this conversation far longer than an adult’s lecture. The authors of the McCormick Foundation’s Protocol for a Free and Responsible Student Media argue that “good journalism energizes school culture. It integrates every dimension of school into its function and engages the entire school community in democratic participation.” These benefits go beyond the student participants, they say: “Its peripheral effects on the school community strengthen partnership, participation, accountability, transparency, trust and all other essential components of a democratic school system. Student news media can be a bridge that connects administrators, students and the community in ways that profoundly benefit school culture.” Again, I have seen this in practice. My student journalists, especially the editors, have built trusting relationships with our administration. We have invited them into our classroom to see our staff at work. We have sponsored group discussions about how to cover controversial issues and explained the ethical processes editors use to make difficult decisions. We have put systems in place to ensure accuracy, yet also shared our corrections policy when, inevitably, mistakes happen. This doesn’t mean that the adults in our community always like the students’ coverage. For example, they have published editorials critical of various policies and changes at the school, and criticism is never easy to read. But that, too, is a crucial democratic understanding. One of the most cherished roles of the United States' free press is as a watchdog of the powerful. In the ruling for Dean v. Utica, the judge wrote that a key role of journalism, whether professional or scholastic, is to provide independent information so citizens can reach their own conclusions. "It is often the case that this core value of journalistic independence requires a journalist to question authority rather than side with authority,” the ruling states. "Thus, if the role of the press in a democratic society is to have any value, all journalists — including student journalists — must be allowed to publish viewpoints contrary to those of state authorities without intervention or censorship by the authorities themselves. Without protection, the freedoms of speech and press are meaningless and the press becomes a mere channel for official thought." Do we want our students to learn to accept authority without question, or do we want them to learn to think critically and dig deep to find answers? If we want critical thought and decision-making as citizens, we must model this in high school. The core values that lie behind this watchdog role are, according to journalist and professor Lou Ureneck, idealism and skepticism. "I try to teach students to challenge authority by asking hard questions," he writes. "I want them to develop a strong sense of skepticism. In a sense, I’m trying to acculturate them into the profession of journalism. [Idealism and skepticism] may seem oppositional, but in our craft their pairing can offer us a potent way to engage the world. For young journalists, these two values inspire as well as energize them to do useful, even penetrating, work." In the Protocol, Frank LoMonte argues that a free student press brings grievances to the surface and promotes civility: "Students seek out the uncensored venue of social networking sites to criticize school policies and personnel because schools offer no meaningful alternative forum for them to be heard. Online ‘drive-by’ grievances can and should constructively be channeled into peer-moderated student media where discussion can occur civilly but without undue restraint." And what happens if the students mess up? What if they misreport something or fail to seek the other side or make a choice to report on something that perhaps is a bit much for a high school readership? A good adviser will raise red flags throughout and offer suggestions, but ultimately the students make a choice and must live wth the consequences. Not in terms of punishment, but in terms of having to be accountable and make amends. Mistakes are powerful. We learn the most when we fail, and we owe it to our students to let this happen. A free student press is a powerful tool. Whether uncovering difficult truths in the community that adults may not want to hear but probably need to or reporting on the latest softball triumph, journalism students are learning how to be citizens and modeling citizenship to their peers. And as far as I’m concerned, informed and active citizens are the only superheroes we need. |

About“And though she be but little, she is fierce!” -A Midsummer Night’s Dream Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed